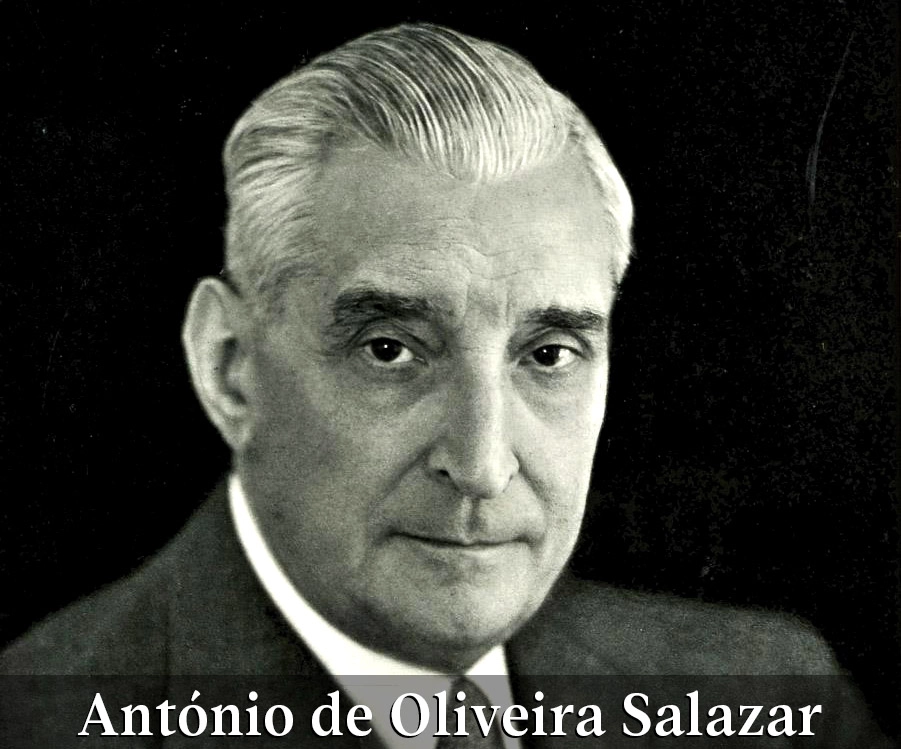

Humble Beginnings: Antonio Salazar’s Early Life

Antonio de Oliveira Salazar was born on April 28, 1889, in the small village of Vimieiro, about 200 kilometers north of Lisbon. He was the son of a farm worker and grew up in a poor household with four older siblings. Despite these humble origins, Salazar showed great promise. In 1910, he began studying law at the University of Coimbra, Portugal’s oldest university, where he quickly earned a reputation as a talented and ambitious student. He became a professor of economics and finance, fields in which he would later be a successful politician.

Political Chaos in the Early 20th Century: 44 Governments in 16 Years

The period after the fall of the Portuguese monarchy in 1910 was marked by extreme political instability. Between 1910 and 1926, Portugal experienced 20 military coups and saw 44 different governments come and go. The constant change led to economic troubles, including rising national debt and increasing social unrest. This chaos created the conditions for a military coup on May 28, 1926, which ended the First Republic and established a military dictatorship.

Salazar’s Rise: Financial Expert to Key Government Figure

Following the 1926 coup, the new military rulers appointed the 39-year-old Salazar as finance minister. His task was clear but difficult: prevent the collapse of the state and stop the forced sale of Portugal’s overseas colonies to cover debts. Salazar introduced strict economic policies:

reducing food imports

increasing exports

raising taxes

freezing wages

controlling prices

These measures caused hardship among ordinary people, as food became scarce and expensive. Public works were postponed, and government spending was cut to a minimum.

Salazar’s policy in the Estado Novo was marked by the persecution of political opponents and by balancing the different interest groups that supported the regime’s power: the Catholic Church, the military, the economy, the large landowners, and the colonies.

Economic Success Explains Salazar’s Rise in Influence

Despite the difficulties faced by many Portuguese, Salazar’s tough policies succeeded in stabilizing the country’s finances. Within his first year, the government recorded a budget surplus and began paying down foreign debt. Importantly, the threat of selling off the colonies was averted, which increased Salazar’s standing among military leaders and the political elite. His control over Portugal’s economy grew, and he established what some called a “financial dictatorship,” overseeing every government department’s spending.

From Finance Minister to Prime Minister: The Rise to Power

On July 5, 1932, Salazar was appointed Prime Minister. His reputation as the man who saved Portugal’s finances and preserved its empire earned him broad support. At this time, Portugal still held significant colonies across Africa and Asia, including Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Goa, Macau, and East Timor. Despite its colonial holdings, Portugal was one of Europe’s poorest and least developed countries, lacking the resources and capital to modernize its economy or colonies.

Portugal Under Salazar Compared to Other European Dictatorships

During the 1930s, fascist leaders gained power in nearby countries: Mussolini in Italy (since 1924), Hitler in Germany (since 1933), and Franco in Spain (since 1936). Salazar’s regime shared some features with these authoritarian governments but was more cautious and less focused on mass rallies or a personal cult. He rarely spoke directly to the public, preferring parliamentary speeches and radio broadcasts. His regime did adopt some fascist symbols, such as the Roman salute from Mussolini, but rejected Nazi racial laws and openly protected Portuguese Jews living in Germany.

Portugal’s Neutrality During World War II

When World War II began in 1939, Salazar kept Portugal neutral, navigating a difficult path as much of Europe was engulfed in violence. As the war progressed and it became clear in the early forties, that the Allies would defeat Hitler, he shifted his alliances towards them, granting Britain and the United States permission to establish military bases on the Azores. These bases were crucial for the Allied war effort in the Atlantic. On May 25, 1945, as the war ended, Salazar was publicly celebrated in Lisbon, seen by many as a leader who had preserved peace and stability without direct involvement in the fighting.

Credit: Museu de Fotografia da Madeira - Atelier Vicente’s.

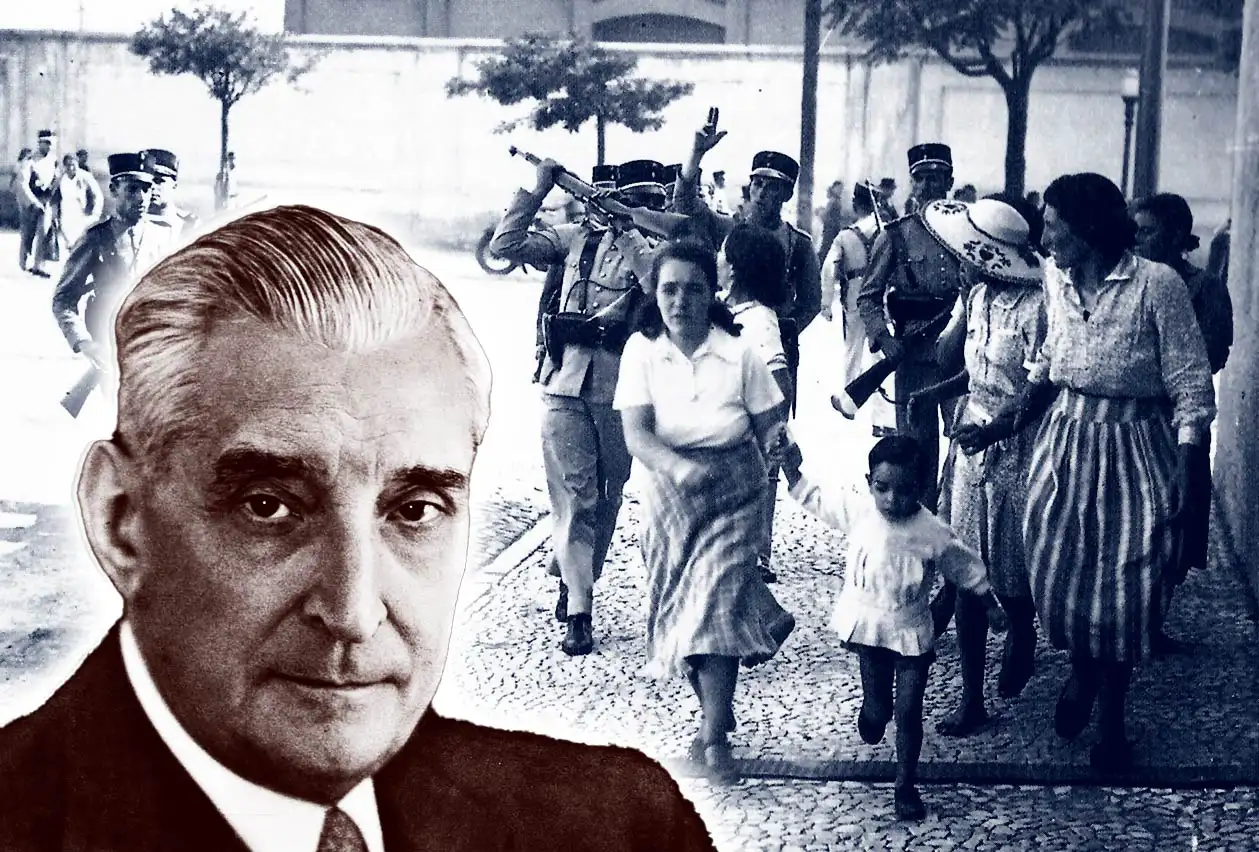

Repression and the Secret Police

Salazar’s regime was highly repressive. The political police, known as the PIDE (from 1969: DGS), monitored and silenced dissent. The PIDE worked closely with intelligence agencies in Western Europe and the United States, including the CIA, to track Portuguese exiles and opposition figures. One of the regime’s notorious prisons was the fortress in Peniche, north of Lisbon, where political prisoners were held, often subjected to torture and harsh treatment. Anyone opposing the regime risked arrest, torture, or worse.

The Colonial Wars: A Struggle to Hold Empire

In 1960, as many African colonies gained independence, Portugal remained determined to keep its colonies. The colonial wars began shortly after, with uprisings in Angola in 1961. Armed groups attacked farms and settlers, leading to violent conflicts. Portugal’s military was unprepared for a long war. Soon, fighting spread to Portuguese Guinea and Mozambique, turning into three-front wars thousands of kilometers from Lisbon. These conflicts involved serious human rights abuses, including violence against local populations.

Loss of Lives in The Portuguese Colonial Wars

The Portuguese Colonial Wars (1961–1974), fought under the Estado Novo, caused significant loss of life, both military and civilian.

Portuguese Soldiers: 8,000 to 10,000 Portuguese military personnel died.

African Fighters (from liberation movements): Estimates vary, but roughly 20,000 to 50,000 fighters from movements such as: PAIGC (Guinea-Bissau), MPLA, FNLA, UNITA (Angola) or the FRELIMO (Mozambique) were killed.

Civilians: Civilian deaths (Portuguese settlers and Africans) are harder to estimate, but likely tens of thousands more died due to violence, famine, displacement, and disease related to the wars.

Salazar’s Decline and the End of His Rule

Salazar spent the summers of his later years at a fortress near Cascais. In August 1968, at age 79, he suffered a severe stroke that left him unable to govern. Despite this, the government concealed his condition for weeks, and a new leader, Marcelo Caetano, was appointed in September 1968. Caetano continued Salazar’s policies with similar firmness but lacked his predecessor’s popularity. Salazar died on July 27, 1970, ending the life of the man who ruled Portugal for over four decades.

The Carnation Revolution: The Fall of the Dictatorship

On April 25, 1974, a peaceful military uprising known as the Carnation Revolution brought an end to Portugal’s dictatorship after nearly 50 years. Soldiers took control of Lisbon and were greeted with enthusiasm by citizens, who placed carnations in the soldiers’ rifles as a symbol of peace. The regime collapsed without bloodshed. The revolution led to the establishment of a democratic government and the end of colonial wars. Today, the anniversary of the Carnation Revolution is a national holiday, symbolizing Portugal’s commitment to democracy and freedom. The Carnation Revolution led to the rapid decolonization of Portuguese colonies, ending decades of colonial rule in Africa and Asia.

Comments