On April 4th, 1931, the Madeira uprising - also known as the Island Revolt, or the Revolt of the Deported - unfolded in Madeira. The uprising was a military revolt against the Ditadura Nacional (1926–1933), which had monopolized grain imports. This policy caused widespread food shortages, worsened by the effects of the Great Depression two years earlier.

Evolution of the Portuguese State Since the 19th Century

Constitutional Monarchy – 1820–1910: Monarchy under the House of Braganza with a constitutional framework.

First Portuguese Republic – 1910–1926: Proclaimed after the revolution, marked by political instability.

Ditadura Nacional (National Dictatorship) – 1926–1933: Military-led authoritarian transitional regime.

Estado Novo (New State) – 1933–1974: Salazar’s corporatist and highly centralized dictatorship regime.

Roots Of The Madeira Uprising

The roots of the Madeira uprising trace back to the "Revolta da Farinha" (Flour Revolt), a popular movement opposing the National Dictatorship in early February 1931. Economic problems worsened due to the Great Depression (1929). Money sent by relatives in Brazil stopped, and unemployment, which was already high, increased even more.

These difficulties caused growing anger and frustration among the people. Government measures to centralize cereal imports led to flour shortages and bread price increases, making bad things worse.

On January 26, 1931, the government published in the Official Gazette. decree 19.273 (better known as the "Hunger Decree") which ended the free importation of wheat and flour, creating a monopoly regime controlled by a group of milling factory owners (or millers). The practical effect of this decree would be the almost total suspension of flour importation and the consequent increase in the price of bread.

Revolta da Farinha, Wikipedia

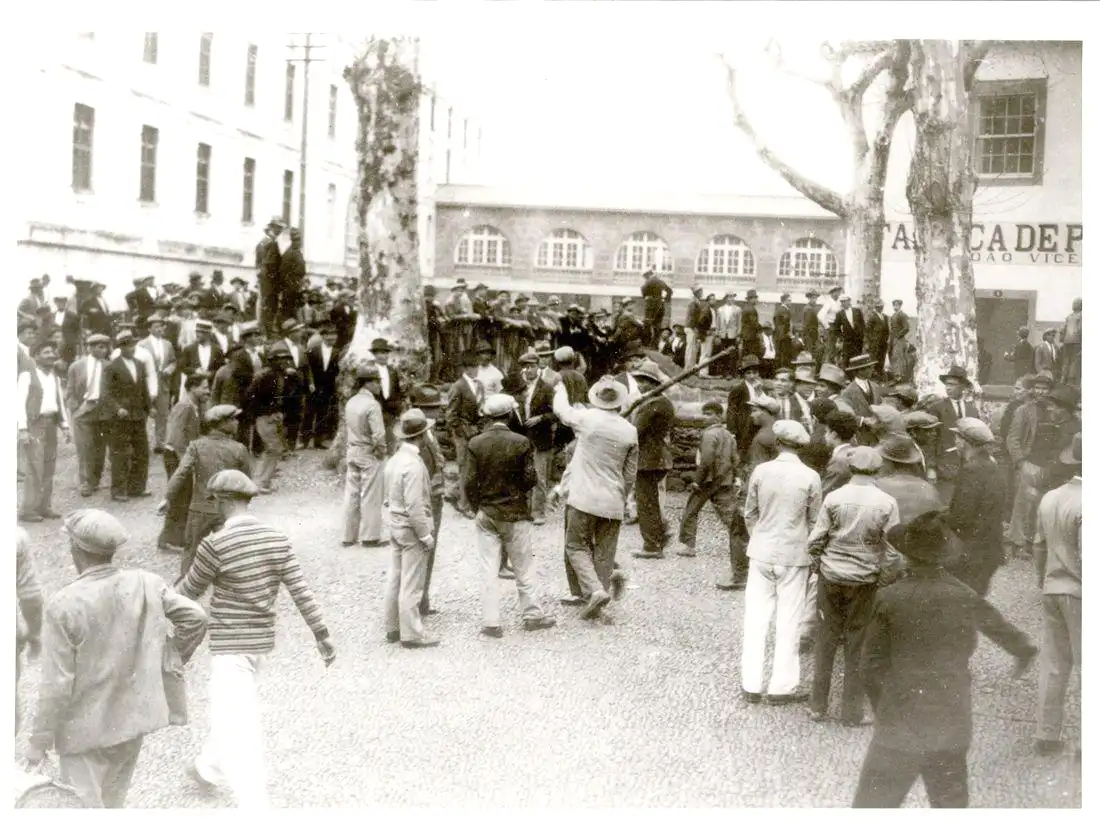

During the Flour Revolt, Madeirans took to the streets to express their anger, organizing strikes, riots, and occasionally attacking grain-related infrastructure such as mills.

The Madeira Uprising Unfolds

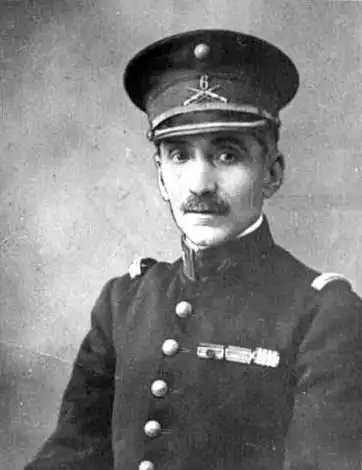

On Madeira, military officers and civilian politicians opposed the regime. Most notably General Adalberto Gastão de Sousa Dias, who previously played a great role in defending the First Republic and was one of the most consistent oponents of the Ditadura Nacional. He had been exiled to Madeira in 1930.

Unlike in the Azores, where rebellious military forces surrendered without popular support, the Madeira rebels received backing from the common people.

The uprising started on April 4th, 1931, when in the early hours, a group of insurgent officers - among them Manuel Ferreira Camões, a medical lieutenant who gave the uprising its military dimension, seized the Palácio de São Lourenço in Funchal and arrested senior government officials.

The revolt declared itself underway, and a provisional government - the Junta Governativa da Madeira - was formed. Adalberto Gastão de Sousa Dias was placed in charge of executive and legislative powers.

During the first weeks, the insurgents - who were very popular among Madeirans, issued decrees, they:

declared the cereal‑monopoly decree invalid.

granted emergency loans to Madeira’s embroidery industry.

tried to stabilise prices of key goods.

Their goal wasn’t only island politics, but to challenge the central regime and invoke constitutional government. They wanted Portugal’s government to operate according to law and democracy, rather than being run by a military dictatorship or authoritarian rulers.

Furthermore, many hoped that such revolts would grow into something bigger, ignite a nationwide revolt and eventually force the Ditadura Nacional to give up power. The goal was to allow Portugal to return to the First Republic.

Government Sends Soldiers, Warships and Seaplanes

Despite its initial success, the revolt did not spread enough to threaten the regime nationally. In response, the government in Lisbon decided to take action. By the end of April, Portugal’s under-resourced military managed to turn requisitioned ships into a small naval force and sent troops to the island.

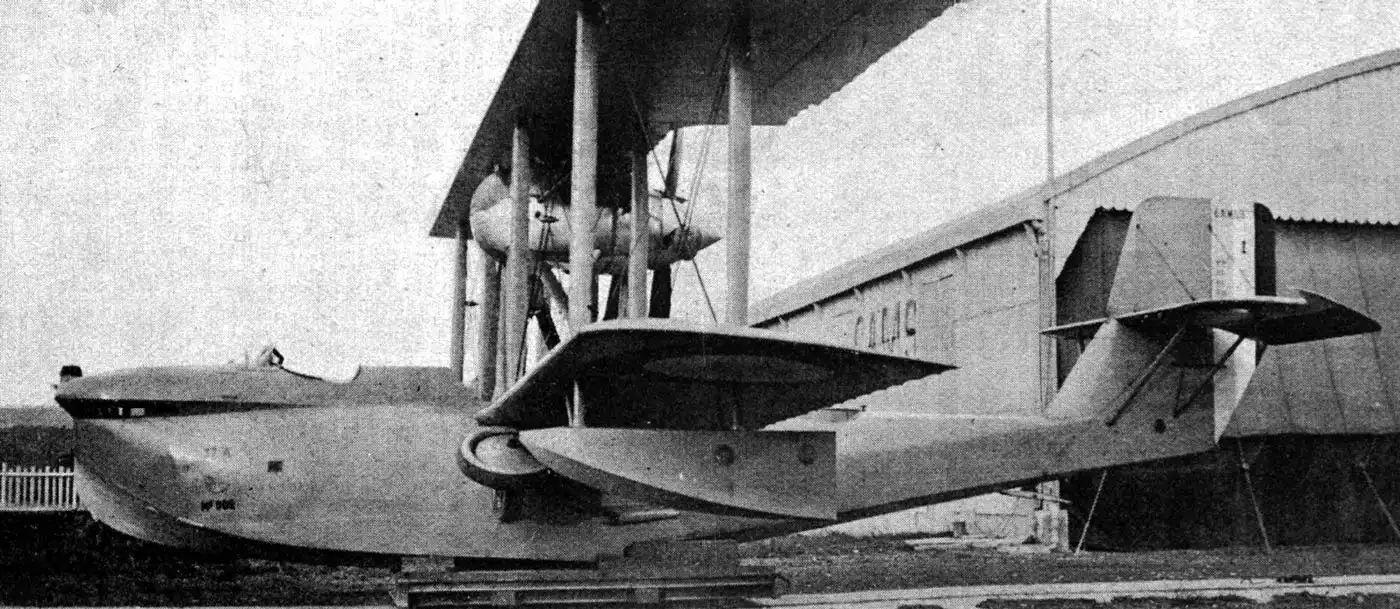

On April 24, seaplanes carried by the SS Cubango left for Madeira. They arrived two days later and flew over Madeira on reconnaissance and attack missions, also dropping pamphlets as part of a psychological campaign. Meanwhile, warships anchored in Funchal Bay, and soldiers landed at Caniçal on the east coast.

Faced with the scenario of armed conflict, foreign nations with interests in the region mobilized resources, and on April 8th the British cruiser London was already anchored in Funchal Bay, with the aim of protecting British subjects and their property.

Revolution Declared Unsuccessful by May 2nd

The revolution lasted seven days. Despite efforts by the government to prevent foreign military intervention, it was ultimately suppressed by May 2nd.

General Sousa Dias and many other rebel soldiers were sent to Cape Verde. Although the local rebels fought bravely, they did not have enough weapons, were fewer in number, and lacked supplies.

Furthermore, the Ditadura Nacional received support from the United Kingdom, which believed its interests were better represented by the undemocratic regime than by the First Republic that preceded it.

Madeira Uprising's Initial Triumph

The initial triumph of the Madeira Uprising showed the strength of local opposition against Portugal’s unstable government in 1931. Protesters and soldiers quickly took control of key areas, giving hope for change. This early success inspired people across the island. It became a symbol of courage and resistance in Madeira’s history.

In 1977, Sousa Dias, evoked as «one of the greatest figures of the resistance» and an «example of the highest moral virtues», would be reinstated posthumously, by Decree-Law No. 232/77, in his post of General, with all the inherent honors and the right to decorations and honorary degrees that he possessed.

Historical Significance Of The Madeira Uprising

The Madeira Uprising of 1931 was significant because it reflected widespread opposition to Portugal’s First Republic and the rise of the military dictatorship. Citizens and workers protested against economic hardship and political instability.

Although quickly suppressed, the uprising highlighted regional discontent and inspired later resistance movements against authoritarian rule.

It shaped Madeira’s identity and also marked its role in national politics, showing that even remote regions could influence Portugal’s political future.

Historically, the Madeira Uprising remains one of the most significant insurrections against the Ditadura Nacional.

Comments